Alabama native tasked with increasing School’s enrollment, graduation numbers

By David Miller

TUSCALOOSA, Ala. – With more than 45 years of classroom and administrative experience, Dr. Sharon Porterfield will add a familiar role to her distinguished career in education: recruiter.

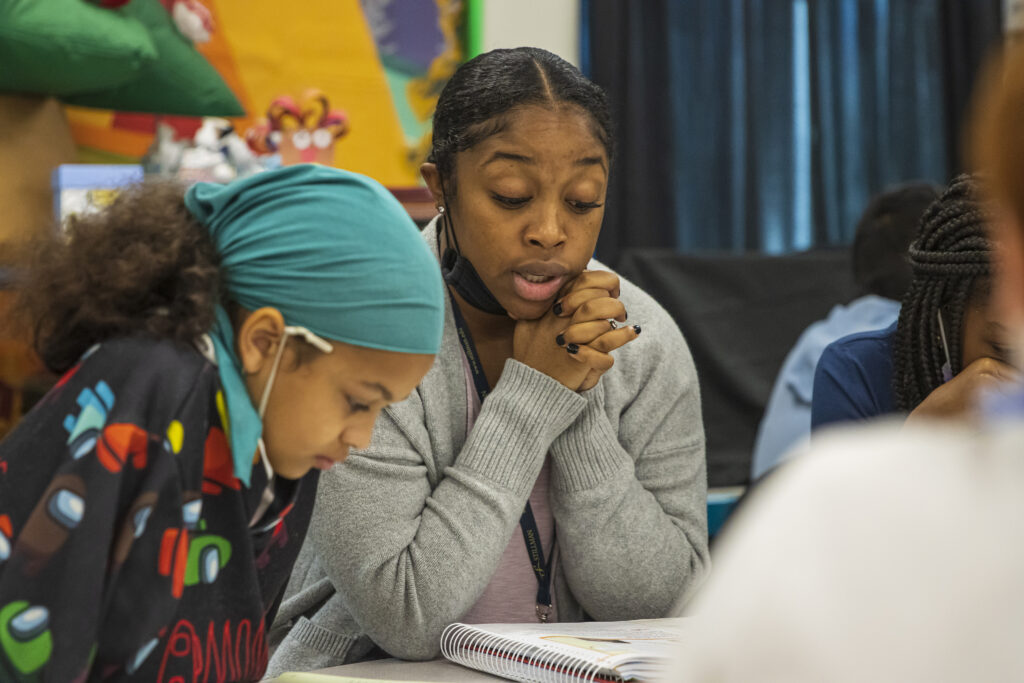

Porterfield, recently named dean of the Stillman College School of Education, is tasked with revitalizing the program to produce more certified teachers and to position students from other majors into teacher pipelines.

Graduating more certified teachers will help address the shortage of K-12 educators in Alabama, which has seen a spike in teachers leaving the field earlier than before and a sharp decline at the other end of the funnel; the rate of students earning a college degree in education has fallen 58% since 2003, according to the Alabama Commission on Higher Education.

There are a myriad of issues affecting the declining pool of teachers, such as burnout, pay, state testing, and the COVID-19 pandemic. State and local school administrators are trying to address these issues through temporary teaching certifications, sign-on bonuses and incentives for STEM educators.

Teacher education programs play an important role in stemming this shortage, both in recruiting new students into elementary and secondary education majors, retaining and graduating them, and equipping students in other majors for a career in teaching.

Porterfield, who previously chaired the Division of Education at Miles College, said her role at Stillman is an “opportunity to make a difference,” and it begins with a clear message to Stillman students: you are needed.

“[Stillman] wants to graduate the best teacher candidates and fill these voids,” Porterfield said. “And it starts with recruitment.”

Porterfield is already putting her recruiting plan into action; she is working to create a School of Education pipeline with Maranathan Academy in Birmingham, and she has formed a teacher advisory committee comprised of educators and administrators from both Tuscaloosa and Birmingham. The goals of the advisory committee are to identify issues affecting teacher candidates and ultimately get Stillman graduates hired in districts in both areas, and to encourage high school juniors and seniors to consider the education path, Porterfield said.

“The committee is extending a hand to say, ‘work with me … let’s put these teachers in our schools and make sure they’re properly trained and utilizing all the resources available,’” Porterfield said. “That’s critically important for the School of Education.”

Porterfield previously worked with the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Urban Teacher Enhancement Program to help recruit highly qualified educators to teach in at-risk schools. Her role on the project was to develop the project planning timeline and feasibility of partnering with other small HBCUs.

Porterfield’s recruiting work aligns closely with Stillman President Dr. Cynthia Warrick’s initiative to not only improve the School of Ed’s graduation numbers and career prospects for its students, but for all Stillman graduates. Warrick recently announced a new campus-wide requirement that Stillman students take 18 credit hours in the School of Education, regardless of major. Warrick cited the starting base pay for new certified teachers in Alabama, which, after a recently approved adjusted pay scale, is just under $42,000. There are also incentives for teaching at “hard to staff” schools, like student loan forgiveness and pay supplements.

Additionally, under Alabama’s new Teacher Excellence and Accountability for Mathematics and Science (TEAMS) program, new secondary teachers in math and science in hard-to-staff areas could make as much as $47,000 annually. Some teachers in this program could make up to an additional $20,000 annually.

By accruing the additional credits, graduates from other majors can begin teaching immediately while achieving certification through an alternate route. This career pathway is currently being pitched to Stillman psychology majors, who are encouraged to take 18 hours in collaborative special education, an area facing such extreme shortages that the state has created an “emergency” three-year pathway for four-year degree holders to begin teaching immediately.

“The same goes for biology majors who may face some uncertainty in what they want to do once they graduate – work in a lab? Perhaps go to graduate school?” Porterfield said. “What we’re telling them is that, even if you don’t plan to teach, give yourself that option and position yourself for certification. You never know what the future may hold.”