- About Us

- Admissions & Aid

-

- Academics

-

- Student Life

- Athletics

Snedecor Hall

Stillman College

3601 Stillman Blvd.

Tuscaloosa, AL 35401

Monday – Friday:

8:00am – 5:00pm

Phone: 205.349.4240

Email: alumniaffairs@stillman.edu

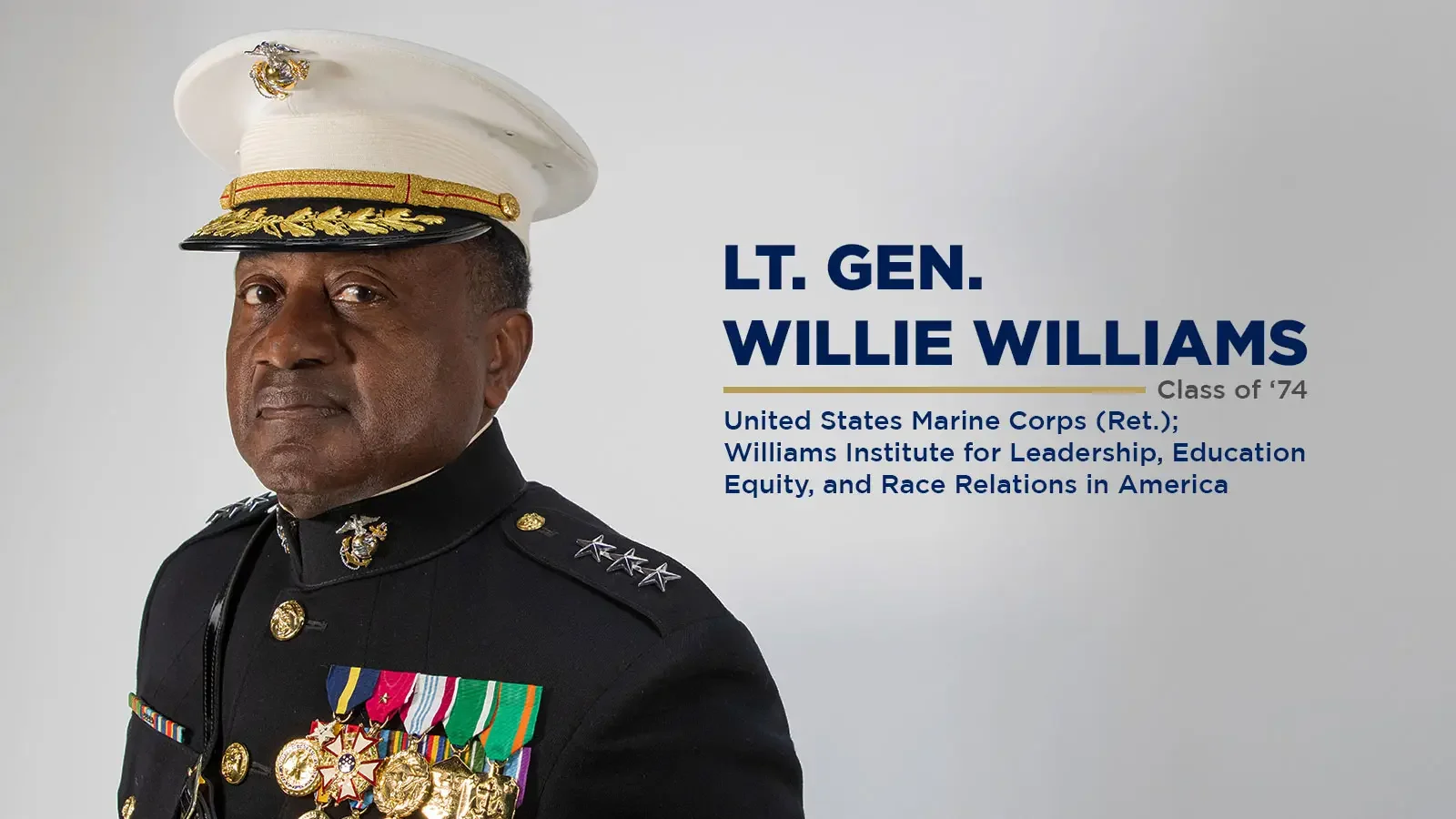

Stillman College has been preparing leaders who make a difference in their professions, their communities and the world since 1876. We have many remarkable alumni/ae, some of whom are profiled here. Our graduates have distinguished themselves in major fields ranging from military, education and law to medicine and business. Here are some of Stillman’s more notable Stillmanites.

Willie J. Williams had no intention of pursuing a college degree.

He grew up in a segregated community in Moundville, Alabama. Affording college would be difficult for a family “just trying to survive.”

Though he was an honors student, Williams wouldn’t apply to colleges or universities.

“I didn’t have the resources to think about college, so I didn’t plan for it,” Williams said.

Faculty and staff in his high school, many of whom were alumni of Stillman College, took notice of his potential for higher education. They began working with admissions staff at faculty to create scholarship and work-study aid packages for Williams, who agreed to consider Stillman if he could attend without the financial burden.

“I guess they submitted my application for me because I don’t remember doing it,” Williams says jokingly. “I don’t know who my high school teachers talked to at Stillman, but at my graduation, when they read my name they announced that I’d accepted scholarships to Stillman.

“So, when people ask why I chose Stillman, I tell them ‘Stillman College chose me.”

Williams would earn a bachelor’s degree in business at Stillman in 1974 before embarking on an impressive and trailblazing career in the United States Marine Corps, where he would ascend to the rank of lieutenant general, only the third African-American Marine at the time to wear the rank of three-star general. He also served as chief of the Marine Corps staff before retiring in 2013.

Williams’ career as a Marine Corps officer would not have materialized if not for Stillman College, as military officers must possess a college degree. He says the support from Stillman alumni and high school faculty to get him to Stillman grew once he enrolled; faculty, staff and classmates all played roles in helping Williams navigate a difficult schedule of classes, a work-study position, and a full-time job at a nearby textile mill. Faculty members would coordinate with students to share lecture notes if Williams missed a class; friends would make sure he was up and ready for work. Friends would also make sure he balanced social life into his schedule.

“It was pretty tough there for a while,” Williams said. “There wasn’t much rest. But to have faculty like Dr. (Albert) Sparks take such an interest in me, to be flexible like that, was pretty symbolic of how much the faculty cared about the students.

“I use their example now when I’m mentoring kids and as I’m mentoring others as well – those teachers, from my high school to Stillman College, were some of the first to take away my excuse for failure, and they facilitated my success with the Marines.”

Williams credits his faith in God for directing his and others’ footsteps, according to the “Will of ‘I AM’” in the Book of Exodus. He is now working to remove barriers for current Stillman students through the Williams Institute for Leadership, Education Equity and Race Relations in America, which launched in in 2021 at Stillman College. The Williams Institute is an effort to afford Stillman College and the community extensive access to scholarly research, interdisciplinary study, discourse and debate, and advocacy on cutting-edge issues related to leadership, education equity, and race relations in America.

The Williams Institute also oversees student-focused programs like the Black Male Initiative, which aims to increase matriculation, retention, and graduation rates for males of color. Williams also serves on Stillman’s Board of Trustees and is a

consistent presence on campus for Williams Institute and community

events, and to provide mentorship to Stillman students.

“There’s a void I see coming in our society for leaders of character – dedicated and disciplined – in order to move forward, and I think this Institute will try to instill some of those qualities,” Williams said. “I did not conceptualize it in the context of what we’re seeing with our programming and the results we’re seeing today, but I knew that, based on my experiences, I could facilitate success in their lives.”

Though not fully retired – Williams is president and CEO of a consulting firm – his proximity to campus affords him the opportunity to engage Stillman students. He often reflects on the similarities between his experiences as a young student and those of the young men he’s mentoring. Williams recalls learning of former Stillman student Gilbert “Hashmark” Johnson, who served in three branches of the military over 32 years, including 17 in the Marines, where he became one of the first Black drill instructors.

Williams shared his appreciation for Johnson’s career and influence during a recent meeting with Stillman students.

“As I look back and think of where Hashmark Johnson came from – he went through Marines boot camp at 37 years old – he helped set the path for me,” Williams said. “Though I didn’t know it [while at Stillman], when I finally became aware of it and reflected on it, for me to do anything less than my very best would be an insult to Hashmark Johnson.

“One of the young men [at Stillman] looked at me and said ‘I feel the same way about you. If I don’t do my best, I would let you down.’ That touched me in a very profound way. They told me, ‘we stand on your shoulders.’ And I told them, ‘I’m gonna give you the strongest shoulders to stand on that I can.’”

As a young child, Keisha Lowther would practice vital screenings on her dolls. She would routinely tell her parents, both of whom were educators, that she wanted to be a doctor, an ambition they would support and encourage.

Lowther carried that ambition throughout childhood, despite the numerous societal and professional obstacles facing Black women who aspired to work in medicine.

“I just loved how nice and kind physicians were from my early years,” Lowther said. “I wanted to be like them.

I wanted to help people.”

Lowther would achieve that dream – and much more. Dr. Lowther has owned and operated a primary care practice and currently serves as chief medical officer of Whatley Health Services in Tuscaloosa, a “full-circle” appointment for Lowther, who served as both an intern and primary care doctor in rural Greene County after completing her residency at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Before she would complete her MD at Meharry Medical College, Lowther would earn a degree in biology at Stillman College, a launchpad for her career, both before and after medical school.

However, her path to Stillman nearly didn’t materialize.

Lowther attended John Carroll Catholic School in Birmingham, a school with traditionally low enrollment of Black students. She was eager to attend a HBCU and didn’t apply to a Predominately White Institution (PWI).

Her parents were alumni of both Alabama A&M University and Miles College, so she cherished and sought out the cultural dynamics of a HBCU. She was set to attend Xavier University in New Orleans, but an unexpected wait for a dorm room was revealed the summer prior to her freshman year. Lowther and her family “began to panic.”

“But then we heard a radio commercial for Stillman and that they would be at a Presbyterian church in Fairfield for a recruitment day,” Lowther said. “We went there, they had a beautiful display, and I met some upperclassmen. I also met Mr. [Mason] Bonner (then director of admissions) at the fair, and he encouraged us to go visit campus. We drove to Tuscaloosa immediately after, and I fell in love with Stillman.”

Lowther would find everything she needed and wanted to help her reach her career goals: the campus was small but intimate; classmates were friends, and faculty were mentors. Stillman’s agenda was clear: campus was and always will be “home.”

“At home, you’re going to be in an environment where you’re set up for success,” Lowther said. “And it may look different for each student depending on what you want to do, but everything you need is at Stillman – the support, the lifelong friendships, the academic opportunities.”

Most critical in that sphere of support and opportunity at Stillman, Lowther said, was the focus on preparing students for graduate school, from reinforcing the importance of punctuality and professionalism, to setting up mock interviews for jobs and internships.

Lowther credits former professors Dr. Diana Dorai-Raj (chemistry), Dr. Elsa Glover (physics) and Dr. Godwin Ihejeto (chemistry) for setting a standard for excellence across all classes.

“They made sure we had the foundation,” Lowther said. “It wasn’t anything for them to come in on a Saturday to explain things again or provide supplemental materials to help us learn. They made sure I was in a summer program each year – I had one at Yale, one at UAB, and two summers at a pharmaceutical company in New Jersey that eventually offered me a job.

“So, they expected excellence, and if [students] weren’t striving for that, you were held accountable.”

The campus “standard” was a “blessing” at Stillman and helped propel her through medical school. She said her undergraduate experience would have been vastly different at a larger school or PWI. She said more of her friends who enrolled in HBCU pre-med tracks ultimately became physicians, compared to those who attended

PWIs.

“I know that I would not be a doctor if not for the opportunities afforded at Stillman,” she said. “Having that summer at Yale on my résumé, and being able to shadow a pediatrician at Whatley – I’m likely just a number at another institution and would not have had those opportunities.

“Ultimately, if you have a goal, there are people at Stillman and in your community who will help you reach it. I’ll always cherish that.”

Seize each and every opportunity. This ethos is foundational for Joe Hampton’s career in the gas industry, and it’s been a guiding force well before he stepped foot on Stillman College’s campus.

Before he would become president of Spire Mississippi and Alabama, Hampton was a talented high school senior who dreamt of playing college and professional football. Beyond that, he was indecisive about his future.

“Your parents push you to go to school, do your best, and graduate,” Hampton said. “But, like most 17-or 18-year-olds, I didn’t know what I wanted to do.”

One of Hampton’s high school counselors urged him to apply to INROADS Birmingham, a youth development and career readiness initiative that was partnered with Spire, then AlaGasco. The requirements were simple: attend a competitive bootcamp for several weeks and interview with partner companies, and, if selected for an internship, maintain a 3.0 GPA, “be a good citizen, show up on time, and do your job,” Hampton said.

Hampton would first intern at Spire the summer before enrolling at Stillman College, an unforeseen detour from where he’d envisioned his undergraduate experience. Hampton wanted to walk onto the football team at the University of Alabama, where he had a partial academic scholarship offer. Stillman, however, offered Hampton, who finished third in his high school class, a full scholarship through an unexpected source: the Stillman Choir. Hampton sang in the choir at his high school, and after James Arthur Williams, Sr., then director of Stillman’s choir, visited his high school and heard him sing a pair of solos, he offered Hampton full tuition, room, and board.

However, there was a hurdle: Hampton wanted to major in engineering, which Stillman didn’t offer. But, through a dual-degree option with the University of Alabama, Hampton could earn both a degree in physics at Stillman and an engineering degree at UA.

“That Monday, [Williams] was back at my school with the course catalog,” Hampton recalled. “He mentioned the dual-degree and, if I could do it within five years, my scholarship would be covered, even at [UA].”

Hampton would choose Stillman College, an institution that provided the high-level instruction, student supports and campus culture necessary to complete a challenging dual-degree program and balance his internship with Spire.

But it was the direct engagement from faculty and the “family” dynamic of Stillman that were the greatest assets to Hampton’s academic and future business success, he said. He credits a pair of faculty members – Dr. Diana Dorai-Raj and Dr. Elsa Glover – chemistry and physics professors, respectfully, for working beyond the classroom to ensure students learned course material. Hampton said Dorai-Raj and Glover would cook dinner for and tutor he and his classmates – support that would continue beyond his time at Stillman.

“When I got to [the University of] Alabama, it was a culture shock,” Hampton said. “There were four or six students per professor at Stillman, and there were 150 in some of my engineering classes at UA. I was so disconnected. I went about three or four weeks, took a test, and didn’t do well. I remember feeling like I wouldn’t make it. So, I call [Glover] up, and she said, ‘hey, come by the house.’ I take my engineering books, thinking, ‘she’s a physics professor, what does she know about this?’ But she broke it down for me. I went from feeling I’m not going to make it, to being a top student.”

Hampton would earn degrees in physics at Stillman and electrical engineering at UA, capitalizing on the dual-degree option before completing his master’s in business at Troy in 2003. These concurrent enrollments and dual-degree options with UA are still in place and have since grown to include graduate school pathways.

Hampton says Stillman’s many layers of support make it a “hidden gem” among larger HBCUs in the state.

“The closeness, the relationships, the preparation for adulthood – you’ll get direction to help you grow,” Hampton said. “The level of relationships I have at Stillman are second to none. These are uncles and aunts to me, cousins and brothers and sisters. Stillman brings a level of family to the education process that I don’t think you get at many other institutions.”

During his academic and professional career, Hampton has been connected to only one company: Spire. He interned with Spire throughout college and has served as a tactical manager, vice president for field operations in Kansas City, and as president of Spire Alabama and Mississippi, a position he’s held since 2018. The decades-long working relationship is both rare and special, he said. And, like Stillman College, the relationships at Spire have been foundational to his success: the engineer, Ken Smith, who selected Hampton for the INROADS program in 1992, encouraged him to take the VP position in Kansas City – despite Hampton’s reluctance to move out of state – because “it would pay off.” Hampton would later succeed Smith as president at Spire.

The two remain close friends, Hampton said.

“It’s extremely important to not overlook the importance of that first conversation or that first opportunity to engage,” Hampton says. “You never know how someone is viewing you as the next leader.

“I’m looking for the next Joe Hampton [at Stillman]. I want to ensure there are five other Joe Hampton’s to take my seat.”